The CCI and the New Boundaries of Competition Enforcement

The Supreme Court of India (Supreme Court)’s September 2025 ruling has thrown the spotlight back on the uneasy overlap between patent rights and competition law. In the long-running dispute between Ericsson and the Competition Commission of India (CCI) over FRAND licensing of Standard Essential Patents (SEPs), two questions took centre stage: are royalty terms a matter for competition law or patent law, and can private settlements close the door on public scrutiny?

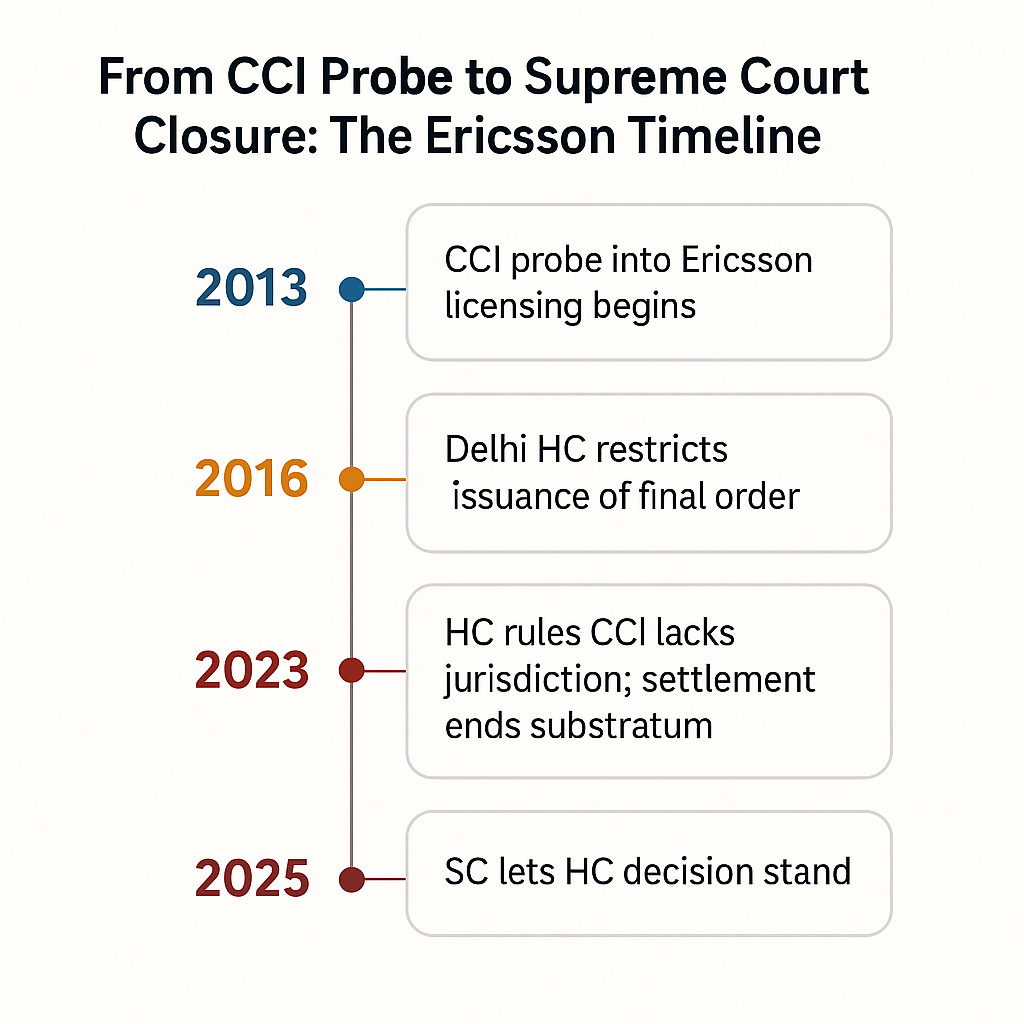

This post looks at both issues. Part I considers the limits of the CCI’s jurisdiction in SEP disputes. Part II explores the role of private settlements in ending competition proceedings. Before we dive in, the infographic below traces the course of the Ericsson litigation through the courts.

Part I: Can the CCI Enter the IP Battlefield? Lessons from the Ericsson Judgment

When Ericsson’s licensing practices were first challenged before the CCI in 2013, the dispute triggered one of the most sensitive questions in Indian regulatory law:

Can the CCI examine allegations of abuse in FRAND licensing of patents, or are such issues reserved for intellectual property (IP) law and the courts?"

Back in March 2016, Ericsson argued before the Delhi High Court that the Patents Act was a complete code governing royalties and licensing terms. The Delhi High Court did not fully oust the CCI, but it did restrain the Director General (DG) from submitting any final investigation report and directed the CCI not to pass a final order until further hearings. In effect, while the DG could continue fact-finding, the investigation was placed under judicial supervision.

In July 2023, the Division Bench of the High Court went further, holding that the CCI lacked jurisdiction altogether. The judgment was decisive: once the informant and Ericsson had reached a settlement, the “substratum” of the CCI’s case had vanished, and in any event the CCI could not pursue such investigations.

In September 2025, the Supreme Court declined to interfere. While carefully leaving questions of law open for a future matter, it effectively let the High Court’s 2023 decision stand.

Implications

Scrutiny of SEPs has narrowed: The ruling limits the CCI’s ability to review licensing markets for SEPs, even in cases alleging excessive royalties or unfair terms. For SEP-heavy sectors such as telecom, semiconductors, and emerging AI standards, this translates into reduced antitrust exposure.

Overlapping regimes remain sensitive: The decision signals judicial caution in areas where patent and competition law intersect.

Part II: Settlements and the Future of Competition Enforcement

The Ericsson case also raised a second issue:

What happens when parties settle while a CCI case is pending?

The Delhi High Court was clear - once Ericsson and the informant resolved their dispute privately, the foundation of the CCI’s case collapsed. The Supreme Court agreed: if the original complainants “have nothing further to say”, then proceedings cannot continue in the abstract.

On its own, this might have been seen as specific to SEP licensing. But the JCB case shows the principle is broader.

The JCB Connection

The CCI first initiated an investigation into allegations that JCB used predatory litigation to sideline its competitor, Bull Machines. After directing a DG probe, the parties privately settled before the case could run its course. In the litigation that followed, the Delhi High Court held that the settlement extinguished the substratum of the dispute, leaving nothing for adjudication, and stressed the sanctity of settlements, warning that keeping proceedings alive after resolution would leave firms under a perpetual “Sword of Damocles.” On appeal, the Supreme Court did not interfere with this order.

Taken together, Ericsson and JCB establish a judicial doctrine: private settlements in disputes with an IP or litigation component can effectively displace public competition enforcement.

The Implications

Private settlements now carry decisive weight: Once parties resolve their disputes, CCI cannot keep investigations alive. This priorities business certainty but limits regulator oversight.

Tension with India’s formal settlement framework: The Competition Act now allows for regulated settlements under the CCI’s watch, with penalty concessions. But these judgments suggest that private, out-of-court settlements may bypass even those formal processes, raising questions about consistency and oversight.

Deterrence could weaken: Large firms might strategically settle with informants to stave off broader scrutiny.

On the other hand, the judgments reflect judicial pragmatism. Courts are reluctant to prolong regulatory proceedings once commercial disputes have been resolved.

Closing Thoughts

The Ericsson saga highlights the fault lines at the IP - competition interface. By narrowing the CCI’s jurisdiction and tying proceedings to private settlements, the courts have redrawn the boundaries of antitrust enforcement in India.

Whether these boundaries become permanent, or are redrawn again by Parliament, the CCI, or future judicial decisions, will shape how competition law interacts with patents in the years ahead.